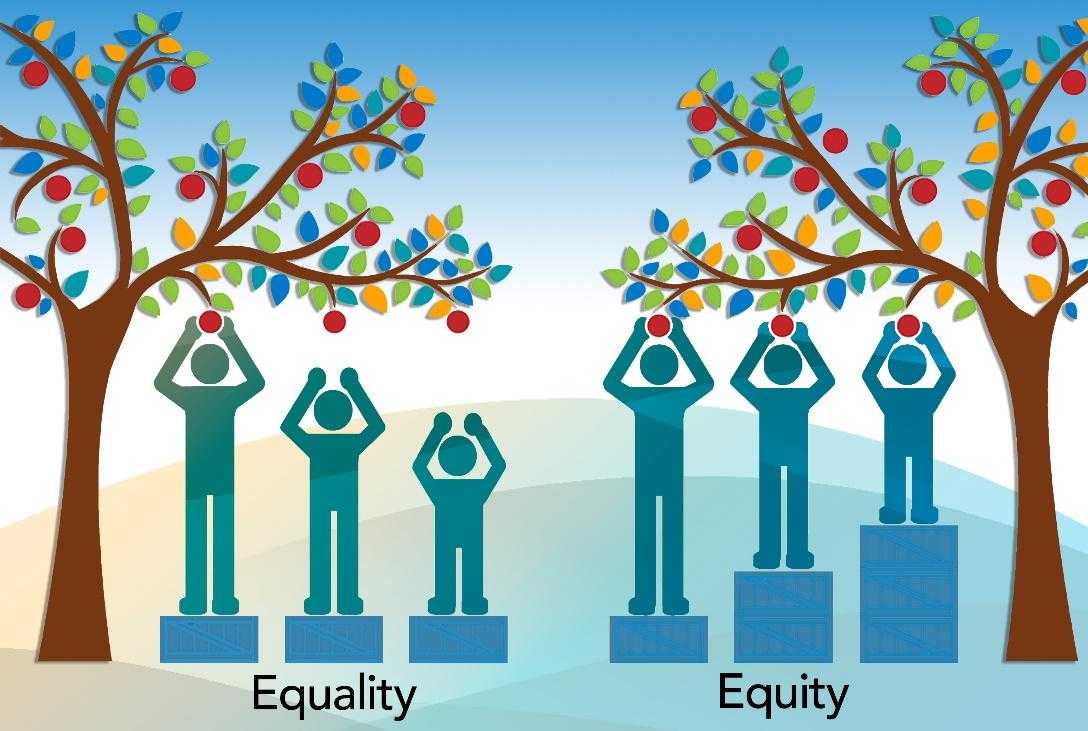

Equity Vs. Equality

Reporting from the All India Political Parties Meet (AIPPM), Akash Iyer delves into how the implementation of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) in India helps the agrarian sector and bridges the socio-economic inequalities.

UBI as an idea of economic stability has been mulled upon by many countries. In most recent memory, the Swiss Confederation’s people rejected the idea of a UBI in a referendum.1 The fad that Andrew Yang managed to create by using the same idea in the Presidential Election of the United States of America (USA)—by promising a thousand dollars per month for every American adult—also eventually died out, leading to him dropping out from the race.2 The earliest reference to such an idea was in a 16th-century novel called Utopia3, befitting the idealism behind UBI. However, when India’s richest one per cent owns over forty per cent of the national wealth, should the country embrace such a concept? Any new policy has three main requirements before it can be smoothly implemented: The first requirement is expert endorsement. India’s economic survey of 2016-17 found UBI as “a conceptually appealing idea” which is potent because of being an alternative to the socio-economic programs intended to reduce poverty.4 Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian’s support for the concept added to this empirical merit of UBI.5 The second requirement is the political viability (read: expediency) of the policy. The recent electoral victory of the Telangana Rashtriya Samithi (TRS) is widely attributed to the implementation of the Rythu Bandhu scheme which granted income support to farmers.6 Sikkim has become the first state to announce a full-fledged UBI scheme, set to be implemented for all its people by 2022.7 The Indian National Congress (INC) has been advocating for UBI or its derivatives for a few years now.8 The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi—which transfers ₹6000 to 120 million Indian farmers—has solidified the party’s standing among the agrarian populace to some extent.9 This shows that parties, unbound by ideological differences, are ready to embrace UBI or its derivatives. The third requirement is that the policy should be in line with the Directive Principles of State Policy of the Indian Constitution; i.e., it should concur with the values that inspired the inception of Indian democracy. UBI satisfies all of those principles which are pertinent to the economy.10 It minimises inequality in income and opportunity because there is stability for all citizens regardless of their fluctuating employment status. It empowers workers to negotiate better working conditions without fear of the inability to make ends meet. It helps agricultural and industrial workers alike to explore cottage industries and co-operatives despite the risks; it virtually establishes a uniform civil code. Additionally, it leads to the decrease in crime rates because less youth adopt nefarious practices due to more stability and opportunities. Furthermore, according to a study by Warwick Business School, women are better investors and money managers than men.11 This finding supports the argument that UBI helps in fighting the patriarchal financial dynamics in Indian households. UBI also holds another distinct advantage that other subsidies and welfare schemes do not share: it minimises the bureaucracy involved and by extension minimises the scope of corruption. It is worth iterating that UBI should also entail the discontinuation of several other mutually non-exclusive schemes. By making the transfers periodical and universal, there is a very slim margin of error in identifying worthy beneficiaries because every adult is considered as one. Even though India was founded on the principle of equality for all its citizens, the principle of equity for the marginalised sections has been a political goldmine for all parties, so much so that “voter bank politics” is now a must-repeat term in the build up to every election. So, equity is something no party can get rid of. Even the BJP, which is emboldened enough to pass legislation that polarises the country, did not get rid of reservations; extending it to the economically weaker sections of all General category people. The question arises: how is giving the rich and the poor the same amount of money in the same frequency in any way equitable? UBI should not be a discrete scheme. Its effort to reduce the economic inequalities will be complemented in tandem by a tax reform as well. The taxes on costlier goods will be hiked to compensate for the money that is going into the pockets of the fortunate. Unlike the government giving money to the underprivileged, this does not involve identifying the ones in need, rather involves identifying the ones not in need of paying more for what they acquire. Such a scheme becomes more pertinent now, especially for the agrarian sector because it shields farmers from instability due to unpredictable monsoons. Every party is promising debt cancellations in their manifestos for elections to the farmers. They do follow through, but the relief farmers get is temporary because the burden on the government to compensate for that debt does not take too long to reflect badly on the farmer it was intended to woo in the first place. Instead of such short-sighted, politically motivated, expedient promises, if the State and Central Governments of India cooperate with synergy to enact a UBI scheme in the country, the backbone of its economy—the agrarian sector—can be revived. Prime Minister Modi’s Achhe din aane waale hain (Good days are coming) promise and his catchphrase since 2014 Abhi ki baar Modi Sarkaar (Modi government hereafter) seem to be godsent encryptions that are meant to be combined as “UBI ki baar Achhe Din” (After UBI come the good days). (Edited by Harsha Sista)

Featured Image: https://www.nwhu.on.ca/ourservices/Pages/Equity-vs-Equality.aspx

SRMMUN 2020

SRMMUN 2020